- Published:

- Written by: B.F.S Industries

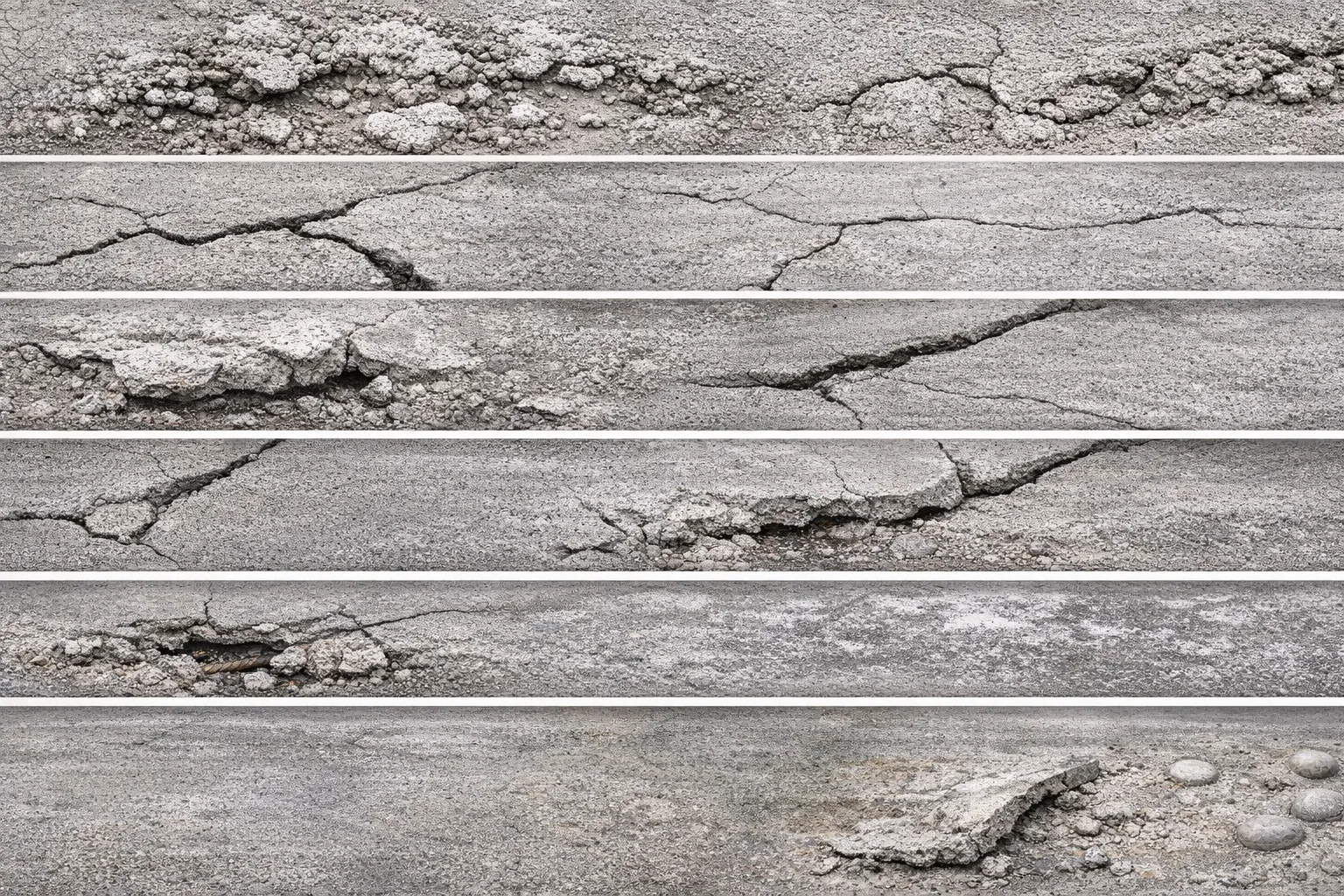

17 Types Of Concrete Cracks and Defects: Causes, Identification, and Prevention

FREE DOWNLOAD – B.F.S. HOLDING

Explore the full spectrum of services and industries covered by B.F.S. Holding.

Concrete is the backbone of modern infrastructure, celebrated for its compressive strength and durability. However, despite its robust nature, it is susceptible to a variety of imperfections that can compromise both the aesthetic appeal and the structural integrity of a building. Understanding the various concrete defects types is essential for civil engineers, contractors, and project managers who aim to deliver high-quality structures that stand the test of time. These defects can range from superficial blemishes that only affect appearance to deep structural fissures that signal potential failure.

The formation of cracks and surface imperfections is rarely the result of a single factor. Often, it is a combination of chemical reactions, environmental stressors, and construction practices that leads to these issues. By identifying the specific characteristics of defects early, construction professionals can implement remediation strategies before minor issues escalate into major liabilities. This comprehensive guide will explore the underlying causes of concrete failures and provide a detailed breakdown of 17 specific defects, ensuring you have the knowledge to diagnose and prevent them effectively. As a partner in construction, BFS Industries is committed to providing the solutions and expertise necessary to minimize these risks from the ground up.

Understanding Concrete Defects and Why They Occur

To effectively manage concrete quality, one must first grasp the fundamental reasons why defects manifest. Concrete is a composite material that undergoes a complex hydration process as it cures. During this phase, the material changes from a plastic state to a solid state, generating heat and undergoing volumetric changes. If these internal forces are restricted or if the external environment imposes stress that exceeds the concrete’s tensile strength, defects will inevitably occur.

How Material Properties Influence Concrete Cracking

The ingredients used in a concrete mix play a pivotal role in its susceptibility to cracking. The ratio of water to cement is perhaps the most critical variable; an excess of water weakens the matrix and increases the likelihood of shrinkage as that water evaporates. Furthermore, the type and quality of aggregates can influence the thermal expansion properties of the cured concrete. If the aggregates react chemically with the cement paste, such as in alkali-silica reactions, internal expansion can shatter the concrete from within. Admixtures, while beneficial, must be dosed precisely. Incorrect usage of accelerators or retarders can disrupt the setting time, leading to weak spots that are prone to cracking under load.

The Role of Workmanship and Formwork Quality in Surface Defects

Even with a perfect mix design, the execution of the pour and the quality of the temporary structure holding the wet concrete are determining factors in the final finish. Poor workmanship, such as inadequate vibration, leads to the entrapment of air pockets and the failure of the aggregate to settle properly, resulting in voids known as honeycombing. Additionally, the condition of the formwork is paramount. If the formwork is not watertight, grout leakage can occur, leaving behind a sandy, unstable surface. Utilizing high-quality systems for Concrete Construction ensures that the concrete remains contained and cures according to design specifications, significantly reducing the risk of surface imperfections.

The 17 Most Common Concrete Cracks and Defects

Identifying defects requires a keen eye and an understanding of how concrete behaves under different conditions. The following sections detail 17 specific types of cracks and defects, explaining their visual characteristics and the mechanisms behind their formation.

Crazing Cracks

Crazing is characterized by a network of fine, hairline cracks that appear on the surface of the concrete, often resembling a map or a shattered windshield. These cracks are typically very shallow and do not extend deep into the concrete mass, meaning they rarely affect the structural integrity of the member. However, they can be visually unappealing, especially on architectural concrete where aesthetics are a priority. Crazing usually occurs when the surface of the concrete dries out much faster than the underlying concrete. This rapid surface drying can be caused by low humidity, high winds, or direct sunlight hitting the fresh pour. It can also be exacerbated by finishing techniques that bring too much cement paste to the surface, creating a weak top layer that is highly susceptible to shrinkage.

Disintegration and Surface Breakdown

Disintegration refers to the physical deterioration of the concrete into small fragments or particles. This defect often starts at the surface and works its way inward, leading to a progressive loss of material. One of the primary causes of disintegration is freeze-thaw cycling. When water enters the pores of the concrete and freezes, it expands, exerting internal pressure that fractures the cement matrix. Over time, repeated cycles cause the surface to crumble. Another form of disintegration is the honeycomb concrete defect, which occurs when the mortar fails to fill the spaces between coarse aggregates. This leaves behind a porous, rock-pocketed surface that is not only unsightly but also allows moisture and aggressive chemicals to penetrate deep into the structure, accelerating further breakdown.

Plastic Shrinkage Cracks

Plastic shrinkage cracks are among the most common issues observed shortly after casting, while the concrete is still in its plastic (wet) state. These cracks typically appear as parallel fissures running across the slab and are caused by the rapid evaporation of surface moisture. When the rate of evaporation exceeds the rate at which “bleed water” rises to the surface, the top layer of concrete begins to dry and shrink before the concrete has gained any tensile strength. This tension tears the surface apart. These cracks are particularly prevalent in hot, windy, or dry weather conditions. Preventing them requires immediate curing measures, such as the application of evaporation retarders or erecting windbreaks to maintain a humid environment around the fresh concrete.

Hardened Concrete Cracks

Unlike plastic shrinkage cracks, defects in hardened concrete occur after the material has set and achieved significant strength. These cracks can be caused by a variety of factors, including thermal stress, drying shrinkage over months or years, or settlement of the subgrade. Thermal cracking is common in massive concrete pours where the core temperature rises significantly due to the heat of hydration while the surface cools down. The temperature differential creates tensile stresses that crack the outer shell. Settlement cracks occur when the ground beneath the concrete slab creates a void or shifts, causing the concrete to bridge a gap it was not designed to span. These cracks are often wider and deeper than surface cracks and may require structural injection repairs.

Scaling and Mortar Flaking

Scaling is the local flaking or peeling of the finished surface of hardened concrete. This defect is frequently observed in driveways, sidewalks, and other outdoor slabs exposed to freezing temperatures. The primary culprit is often the application of de-icing salts. While salts melt ice, they also increase the number of freeze-thaw cycles the concrete undergoes and can increase the osmotic pressure within the concrete pores. Scaling can also be the result of a weak surface layer caused by finishing the concrete while bleed water is still present. This premature finishing traps water just below the surface, creating a fragile layer of mortar that easily flakes off under traffic or weathering.

Delamination

Delamination is a separation of the top surface layer from the main body of the concrete, similar to a blister. This defect is particularly treacherous because the surface may appear sound until it is subjected to traffic, at which point large sheets of paste can detach. The root cause of delamination is often the premature troweling of the surface. If the surface is sealed by a steel trowel before the bleeding process has finished, rising air and water become trapped beneath the densified surface layer. This creates a plane of weakness. When the concrete eventually dries or is subjected to wheel loads, this top layer separates. Detecting delamination often requires sounding the concrete by dragging a chain or tapping with a hammer to hear for hollow spots.

Overloading Cracks

Concrete structures are designed to withstand specific loads, and when these limits are exceeded, overloading cracks appear. These cracks are clear indicators of structural distress and often manifest in patterns related to the type of stress applied. For example, excessive bending moments in a beam will cause vertical cracks near the center of the span at the bottom, or diagonal tension cracks near the supports. Overloading can occur due to changes in building usage, such as placing heavy machinery on a slab designed for light storage, or due to external events like seismic activity or impact. Addressing these cracks typically requires a structural engineer’s assessment to determine if reinforcement or load reduction is necessary to prevent collapse.

Concrete Spalling

Spalling in concrete involves the breaking off of chunks or flakes of material from the surface, often exposing the reinforcing steel beneath. This is a serious defect that compromises the longevity of the structure. The most frequent cause of spalling is the corrosion of the embedded steel reinforcement. When steel rusts, the oxidation by-product (rust) occupies a greater volume than the original steel. This expansion exerts tremendous outward pressure on the surrounding concrete, eventually causing it to pop off. Spalling can also be caused by fire exposure, where the moisture inside the concrete turns to steam and explodes the surface, or by freeze-thaw cycles. Repairing spalling involves removing the loose concrete, cleaning the steel, and applying a repair mortar.

Shrinkage Cracks

While plastic shrinkage happens immediately, drying shrinkage is a long-term process. As concrete cures and dries over weeks and months, it naturally loses moisture and contracts. If the concrete is restrained—for example, by friction with the subgrade or by connection to other structural elements—this contraction induces tensile stress. When this stress exceeds the concrete’s strength, shrinkage cracks form. These cracks are inevitable in many structures but can be controlled. The inclusion of control joints (saw cuts) at regular intervals encourages the concrete to crack in predetermined, straight lines that are easily sealed and aesthetically acceptable, rather than forming random, jagged cracks across the slab.

Structural Cracks

Structural cracks are deep fissures that extend through the full depth or a significant portion of a concrete member, indicating a failure in the load-bearing capacity. These cracks can be caused by design errors, overloading, or settlement of the foundation. Unlike non-structural cracks, which are mostly cosmetic or durability concerns, structural cracks threaten the stability of the building. In vertical elements like columns, these cracks can be vertical or diagonal. Ensuring proper consolidation and using high-quality systems like Concrete Column Formwork during construction is vital to achieve the density and homogeneity required to resist these stresses. Proper alignment and support during the curing phase are also critical to preventing initial structural weaknesses.

Popouts

Popouts are conical-shaped fragments that break out of the concrete surface, leaving small voids. This defect is usually caused by the expansion of a piece of porous aggregate near the surface. If the aggregate absorbs moisture and freezes, or if it undergoes a chemical reaction like the alkali-silica reaction (ASR), it expands and pushes the overlying mortar out. The result is a pockmarked surface. While popouts are generally considered a cosmetic issue, a large number of them can affect the durability of the surface and make it difficult to clean. Using clean, non-reactive aggregates and proper mix designs can significantly reduce the occurrence of popouts.

Low Spots and Surface Depressions

Low spots are areas on a concrete slab that are lower than the surrounding grade, leading to water pooling or “birdbaths.” These defects are typically the result of poor finishing practices or improperly set formwork. If the screeding process is not executed correctly, or if the guide rails for the screed are not level, the surface will be uneven. Low spots can also occur if the subgrade settles unevenly after the concrete has been poured. In industrial floors, low spots can be problematic for forklifts and can create safety hazards. Rectifying low spots often involves applying a self-leveling topping or grinding down the surrounding high spots, both of which are labor-intensive remediation methods.

Efflorescence

Efflorescence appears as a white, powdery deposit on the surface of concrete. It is caused by the migration of soluble salts from within the concrete to the surface. When water moves through the concrete pores, it dissolves calcium hydroxide and other salts. As this salt-laden water reaches the surface and evaporates, it leaves the crystallized salts behind. While efflorescence is generally a cosmetic issue and does not compromise structural integrity, it can be unsightly, particularly on colored concrete or decorative facades. It is often a sign of moisture movement through the concrete, which could indicate drainage issues. Efflorescence can usually be removed with mild acid solutions or pressure washing, but preventing it requires reducing the concrete’s permeability.

Dusting

Dusting describes the development of a fine, powdery material on the surface of hardened concrete that comes off easily under traffic or touch. This creates a constant mess and indicates a soft, weak surface that is not abrasion-resistant. Dusting is often caused by a low-strength concrete mix at the surface, which can result from adding water to the surface during finishing to make troweling easier—a practice known as “blessing” the concrete. It can also occur if the concrete is finished while bleed water is present, or if there is inadequate curing which prevents the surface from reaching its full strength. Carbonation, the reaction of the surface with carbon dioxide in the air before it cures, can also lead to dusting.

Discoloration

Discoloration involves gross color variations on the surface of the concrete, appearing as light or dark patches. This defect does not usually affect the strength of the concrete but is a major concern for architectural projects. Causes of discoloration are varied and include the use of calcium chloride admixtures, variations in the water-cement ratio across different batches, or changes in curing procedures. For example, if plastic sheeting used for curing is in contact with the concrete in some places but not others, it causes differential hydration and color (a phenomenon known as the “greenhouse effect” under the plastic). Even the type of release agent used on the formwork can affect the final color. Consistency in materials and procedures is key to avoiding discoloration.

Curling and Warping

Curling is the distortion of a slab into a curved shape by the upward or downward bending of the edges. This occurs primarily due to differences in moisture content or temperature between the top and bottom surfaces of the slab. If the top surface dries and shrinks more than the wet bottom, the edges curl upward. This creates a gap between the slab and the subbase at the edges or corners, making the concrete unsupported and prone to cracking under load. Warping is a similar phenomenon but is typically caused by temperature differentials. Minimizing curing gradients and using proper joint spacing can help reduce the internal stresses that lead to curling.

Blisters

Blisters are hollow, low-profile bumps on the concrete surface, ranging in size from a dime to a minimal diameter. They occur when air bubbles are trapped under an already sealed, airtight surface. This typically happens when the surface is finished with a steel trowel too early, closing the pores while the concrete is still releasing air or bleed water. The rising air pushes up the skin of the concrete but cannot escape, forming a blister. If the blister breaks, the surface layer collapses. Avoiding blisters involves ensuring that the concrete is not sealed before the bleeding process is complete and avoiding high-speed troweling on air-entrained concrete.

How to Prevent Major Concrete Defects in Modern Construction

Preventing concrete defects is far more cost-effective than repairing them. A proactive approach involves strict adherence to quality control standards throughout the entire construction lifecycle, from material selection to final curing.

Material Control and Accurate Mix Design

The foundation of defect-free concrete lies in the mix design. Utilizing a low water-cement ratio is one of the most effective ways to increase strength and reduce permeability, thereby mitigating issues like shrinkage and freeze-thaw damage. The selection of non-reactive aggregates prevents popouts and chemical expansion issues. Furthermore, the inclusion of appropriate admixtures, such as air-entrainers for freeze-thaw resistance or plasticizers for workability without added water, allows for a more robust material. Regular testing of fresh concrete for slump, air content, and temperature ensures that the mix arriving at the site meets the design parameters necessary to resist concrete cracks.

Quality Formwork, Vibration, and Consolidation

The physical containment and consolidation of concrete are critical in preventing defects like honeycombing, blowouts, and dimensional inaccuracies. Improper vibration is a leading cause of voids; under-vibration leaves air pockets, while over-vibration causes segregation of the aggregate. Equally important is the formwork system. Using precision-engineered systems, such as concrete wall formwork, ensures that the mold is rigid, watertight, and capable of withstanding the fluid pressure of the concrete. This prevents grout loss which leads to honeycombing and ensures the surface finish is smooth and uniform.

Proper Shuttering Removal and Curing Practices

The timing of formwork removal and the subsequent curing process are the final critical steps. Removing shuttering in construction too early can lead to structural cracks if the concrete has not achieved sufficient strength to support its own weight. Conversely, leaving forms in place can aid in curing by retaining moisture. Once forms are removed, immediate and continuous curing is essential to prevent plastic shrinkage and crazing. Whether through wet curing, curing compounds, or covering with protective sheets, maintaining moisture allows the hydration process to continue, building the dense microstructure needed to resist scaling, dusting, and abrasion.

Why Contractors Trust BFS Industries for High-Quality Concrete Workmanship

Achieving a flawless concrete finish is a collaborative effort between skilled labor and superior equipment. BFS Industries has established itself as a cornerstone in the construction sector, providing the tools necessary to eliminate common defects at the source.

The Impact of Proper Formwork Systems on Preventing Concrete Defects

The quality of the concrete surface is a direct reflection of the quality of the formwork used. Old, warped, or ill-fitting timber forms are notorious for causing leakages, offsets, and rough surfaces that require expensive remedial work. BFS Industries provides advanced formwork solutions that are engineered for precision and durability. By using systems that guarantee tight joints and rigid support, contractors can virtually eliminate issues like honeycombing and grout loss. This level of precision reduces the need for surface repairs and ensures that the architectural vision is realized without the blemishes associated with inferior shuttering.

BFS Industries as a Complete Concrete Support Partner

Beyond providing hardware, BFS Industries acts as a technical partner to construction teams. Understanding the nuances of concrete defects types allows their experts to recommend the right forming and shoring systems for specific project challenges. Whether it is a complex high-rise requiring climbing systems or a detailed architectural wall needing a Class A finish, their portfolio covers the spectrum of needs. By integrating high-quality formwork with expert guidance on application and safety, BFS Industries helps contractors deliver projects that are not only structurally sound but also visually impeccable.

Conclusion: Understanding Concrete Defects to Improve Structural Durability

Concrete is an unforgiving material; once it hardens, any errors made during the mixing, pouring, or curing stages become permanent features of the structure. By familiarizing oneself with the 17 types of concrete defects, from the superficial crazing to the dangerous structural cracks and spalling in concrete, professionals can better diagnose root causes and implement effective prevention strategies. Attention to detail in mix design, rigorous quality control during placement, and the use of superior formwork systems like those from BFS Industries are the keys to durable construction. Ultimately, a defect-free structure is not just about aesthetics; it is about ensuring safety, longevity, and value for decades to come.

FAQs

1. Why does concrete develop cracks despite its high strength?

Concrete undergoes hydration, temperature changes, moisture loss, and external stresses. When these forces exceed its tensile capacity, cracks and defects can occur.

2. How does mix design affect concrete cracking?

An improper water–cement ratio or reactive aggregates increase shrinkage, reduce strength, and make concrete more vulnerable to cracking and long-term defects.

3. What role does formwork quality play in surface defects?

Poor or non-watertight formwork causes grout leakage, air voids, and honeycombing, leading to weak and uneven concrete surfaces.

4. What is the difference between plastic and hardened concrete cracks?

Plastic cracks occur shortly after pouring due to rapid moisture evaporation, while hardened concrete cracks develop later from thermal stress, shrinkage, settlement, or overloading.

5. What is the most effective way to prevent major concrete defects?

Accurate mix control, proper vibration, high-quality formwork, and correct curing practices are the most effective methods to prevent concrete defects.