- Published:

- Written by: B.F.S Industries

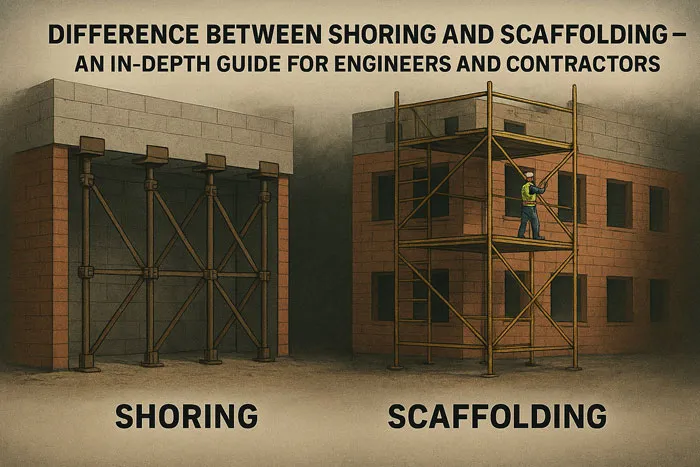

Difference Between Shoring and Scaffolding – An In-Depth Guide for Engineers and Contractors

FREE DOWNLOAD – B.F.S. HOLDING

Explore the full spectrum of services and industries covered by B.F.S. Holding.

In the complex domain of civil engineering and construction, the terms ‘shoring’ and ‘scaffolding’ are foundational, yet they are often incorrectly used interchangeably. While both are critical temporary structures, their fundamental engineering purposes are diametrically opposed. Scaffolding is an access solution, designed to provide a safe, elevated working platform for personnel, materials, and light tools. Shoring, conversely, is a structural support solution, engineered to bear and transfer significant loads to prevent the collapse of a structure or excavation. This guide will provide a detailed technical breakdown of the difference between shoring and scaffolding, examining their design principles, load-bearing characteristics, engineering standards, and practical applications to equip engineers and contractors with the precise knowledge required for safe and efficient project execution.

This podcast provides an in-depth comparison between Shoring and Scaffolding, covering purpose, design, and best practices.

The Role of Temporary Structures in Modern Construction

Temporary structures are the critical, unseen backbone of nearly every construction, demolition, and maintenance project. While the permanent structure—the final building, bridge, or tunnel—gets the attention, it could not be realized safely or efficiently without the calculated use of temporary works. These systems, which include shoring, scaffolding, formwork, and bracing, create safe working environments, provide access to challenging locations, and support permanent structures during their most vulnerable phases. The engineering design of these temporary systems is often as complex and critical as the design of the permanent works, as a failure in a temporary structure can lead to catastrophic loss of life, project delays, and financial disaster.

The importance of this “temporary works engineering” cannot be overstated. This specialized field involves the analysis of transient and construction-specific loads, such as the hydrostatic pressure of wet concrete, the lateral force of excavated earth, or the dynamic loads of equipment and wind on a partially completed frame. These are forces the permanent structure is not yet designed or ready to handle. Therefore, temporary structures like shoring scaffolding systems are not mere accessories but integral components of the construction methodology itself. Understanding their distinct functions, load paths, and limitations is a non-negotiable requirement for site managers, project engineers, and contractors.

Understanding Shoring in Detail

Shoring, in the context of construction, is a purely structural application. Its primary and sole function is to provide temporary support to an element that is otherwise unstable or incapable of supporting itself. This can be due to the element being new (like a concrete slab that has not yet cured), old (a wall being undermined by new excavation), or compromised (a structure damaged by fire or impact). Shoring is the application of an external, temporary load path to ensure stability and prevent collapse. It is a defensive measure, installed to resist vertical (gravity) loads or lateral (horizontal) pressures.

This section will provide a technical examination of shoring, moving from its engineering definition to its practical implementation. We will explore the common types of shoring systems employed in modern construction, from propping up formwork for a high-rise slab (often called falsework) to bracing the walls of a deep excavation. The focus will remain on the engineering principles of load transfer, material science, and the critical design considerations that define structural shoring engineering . Unlike scaffolding, shoring is designed with a singular focus on load-bearing capacity and rigidity, often at the expense of human access.

Technical Definition and Engineering Purpose of Shoring

From a structural engineering perspective, shoring is defined as a temporary system of members (posts, beams, props, and braces) designed to support and transfer significant dead and live loads from an unstable or incomplete structure to a solid, stable foundation. The engineering purpose is to create a temporary, alternative load path, bypassing the unstable element and ensuring equilibrium. This is achieved by introducing members that are strong in compression (vertical posts) or that can resist lateral forces (raking shores or trench bracing). The design must account for the total load, including the dead load of the structure itself (e.g., the weight of wet concrete, which is significantly heavier than cured concrete), and any superimposed live loads from construction activities.

The engineering intent is to maintain structural integrity and, most critically, prevent collapse. This finds application in three primary scenarios. First, in new construction, shoring (as falsework) supports the formwork for elevated slabs, beams, and arches until the concrete gains sufficient compressive strength to be self-supporting. Second, in excavation, shoring systems (like trench boxes or soldier piles and lagging) resist lateral earth and water pressure to prevent a trench from caving in, protecting workers. Third, in renovation or demolition, shoring (like raking shores or facade retention systems) supports existing structures that are being altered, undermined, or partially removed.

Major Types of Shoring Systems

Shoring systems are classified based on their application and the direction of the force they are designed to resist. The most common categories include:

- Dead Shoring (Vertical Shoring or Falsework): This is the most common type used in new construction. It consists of vertical posts, frames, and beams designed to support the dead load of floors, roofs, and concrete formwork from directly below. Modern systems often use high-capacity, adjustable steel props or modular frame systems.

- Raking Shores: This system utilizes inclined members, or “rakers,” to provide lateral support to a wall that is unstable or bulging. The rakers transfer the lateral load from the wall down to a stable foundation (ground plate) at an angle, effectively “propping” it up.

- Flying Shores: Used when the unstable walls of two adjacent buildings are at risk (e.g., during the demolition of a building in a terrace). A horizontal beam, or “flying shore,” spans the open space between the two walls, braced by angled struts, pushing against both walls to keep them in equilibrium.

- Trench Shoring: A specialized category designed to resist the lateral pressure of soil in excavations. This ranges from simple hydraulic “trench jacks” and steel “trench boxes” (shields) that protect workers, to complex, engineered systems of soldier piles, lagging, and walers for deep excavations.

Design Considerations and Load Transfer in Shoring

The design of a shoring system is a critical engineering task that leaves no room for error. The process begins with a precise calculation of all potential loads. For a falsework system supporting a concrete slab, the engineer must calculate the dead load of the wet concrete (e.g., ~150 lbs/ft³), the weight of the formwork itself, and the superimposed live loads of workers, equipment (like concrete vibrators), and potential material storage. A significant factor of safety (often 2:1 or higher, depending on the standard) is then applied to these calculations.

The most important concept in shoring design is the load path. The engineer must trace the flow of force from its origin (the slab, wall, or soil) through every component of the shoring system—the connecting beams, the vertical posts, the bracing—and ultimately into the ground or a permanent structural element capable of bearing the load without failure or settlement. Every component, connection, and foundation point must be verified. Potential failure modes, such as the buckling of a slender post, the bearing capacity of the soil, or the connection’s shear strength, must be analyzed. This is why shoring systems are built from high-strength materials like structural steel H-beams, heavy-duty shoring frames, or high-grade timber.

Understanding Scaffolding in Detail

While shoring’s purpose is to support the structure, scaffolding’s purpose is to support the worker. Scaffolding is a temporary, elevated work platform system designed to provide safe and ergonomic access for personnel, their hand tools, and a limited quantity of materials (such as bricks, paint, or cladding panels). It is essentially a temporary, multi-level working surface that allows tasks to be performed safely at height. Unlike shoring, a standard scaffold is not designed to support, brace, or transfer any load from the primary building or structure it is adjacent to.

This section will detail the engineering and purpose of scaffolding systems, contrasting them sharply with shoring. We will explore the fundamental definition of scaffolding as an access solution, outline the common types seen on job sites, and discuss the design principles that govern its construction. The key differentiators are its load-bearing capacity (which is significantly lower than shoring) and its design focus, which prioritizes human safety, access, and ergonomics through features like guardrails, toeboards, and stable working decks. This is the core of the scaffolding vs shoring distinction.

Definition and Structural Purpose of Scaffolding

The technical definition of scaffolding is a temporary structure used to support a work crew and materials to aid in the construction, maintenance, and repair of buildings and other structures. Its structural purpose is to safely bear its own weight (dead load) plus the intended live load of workers, tools, and materials, and transfer these loads through its vertical members (standards or legs) to the ground. The key word here is intended load, which is defined by the scaffold’s “duty rating” (light, medium, or heavy-duty), and is a fraction of the loads shoring systems are designed to withstand.

A critical, and often misunderstood, structural component of most scaffolding is the tie-in. Scaffolding, being a tall and slender structure, has very little inherent stability against lateral forces (like wind or work-induced movement). To prevent it from toppling, it must be “tied” to the permanent, stable building it provides access to. These ties are crucial for lateral stability, but they are not intended to transfer any vertical load from the building to the scaffold, or vice-versa. This is a fundamental difference between scaffolding and shoring in construction .

Common Types of Scaffolding Systems

Scaffolding technology has evolved from simple timber and frame systems to highly versatile modular systems. The most common types include:

- Supported Scaffolding: The most common category, where platforms are supported by posts, frames, and legs that are built from the ground up.

- Frame Scaffolding: Often seen in residential and light commercial work, it uses pre-fabricated, ladder-like frames that are stacked and braced.

- Modular Systems (Systems Scaffolding): These use individual components (standards, ledgers, transoms, braces) that connect at fixed points (nodes). The ringlock scaffolding system, with its “rosette” connection, is globally popular for its versatility in complex industrial and commercial projects.

- Cuplock Systems: Another popular modular system, detailed in a cuplock scaffold manual, which uses a unique “cup” and “blade” locking mechanism for rapid, secure assembly. Global suppliers, including Pal Scaffolding, provide a range of these systems.

- Suspended Scaffolding: Platforms are suspended by ropes or cables from a stable point above, such as a building’s roof (e.g., window-washing rigs).

- Aerial Lifts: Mobile platforms such as “cherry pickers” or “scissor lifts,” which are not scaffolding in the traditional sense but serve a similar access function.

Design Principles, Materials, and Ergonomics

The design of an engineered scaffolding system is governed by a completely different set of priorities than shoring. The primary focus is worker safety and usability. The design is dictated by standards (like OSHA Subpart L) that specify minimum platform widths, maximum gaps, and the mandatory inclusion of guardrails (top-rails and mid-rails) and toeboards to prevent falls and protect personnel below. The “duty rating” dictates the maximum load and, consequently, the maximum spacing of vertical standards and horizontal bearers.

Materials are chosen for a balance of strength and weight. Steel is common for its strength and durability, while aluminum is often used for lighter-duty or mobile scaffolds where ease of assembly is paramount. The platforms (decks or planks) can be made of wood, steel, or lightweight aluminum/plywood composites. Ergonomics are crucial: the system must provide safe internal access (e.g., integrated ladders or stair towers) so workers are not tempted to climb the exterior frame. When engineers and contractors evaluate the best scaffolding systems, they consider not just load capacity but also speed and safety of erection, adaptability to complex shapes, and the inclusion of these inherent safety features.

Shoring vs. Scaffolding –

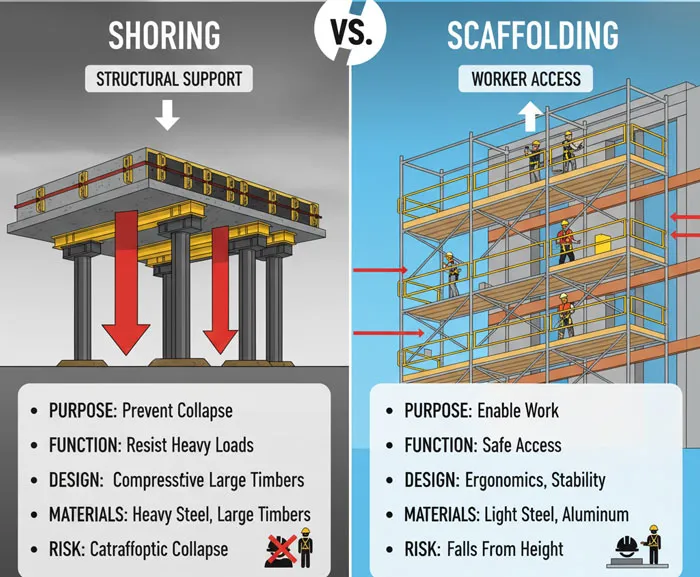

The preceding sections have established that shoring and scaffolding serve two unique, and mutually exclusive, primary functions. The scaffolding vs shoring discussion is not about which is “stronger,” but about which is “correct” for the task. Using one for the other’s purpose is a recipe for failure. The most critical, overarching difference is the flow of force and the intended purpose: one is a structural support solution, the other is a human access solution.

This section will directly compare the two systems. In shoring, the load originates from an external source (the structure being supported) and is transferred through the shoring system to a stable foundation. The shoring system becomes a temporary, load-bearing part of the structure. In scaffolding, the load originates internally (workers and materials placed on the platforms) and is transferred through the scaffold’s own frame to the ground. The scaffold is an adjacent, non-load-bearing (in relation to the building) system. A shoring failure leads to structural collapse. A scaffolding failure leads to a loss of the access platform and a high risk of falls.

Functional and Structural Comparison

Functionally, shoring is a passive, defensive system. It is installed to prevent an unwanted structural event (collapse, caving, or settlement). It is designed to resist forces, often massive compressive or lateral loads, and is engineered for maximum rigidity. Worker ergonomics or access within the shoring system are secondary, if considered at all. The design is pure, brute-force structural engineering, focused on compressive strength and buckling resistance.

Scaffolding, by contrast, is an active, enabling system. It is installed to allow work to be performed. Its function is to place workers and their tools in a safe, ergonomic position. Structurally, its design is focused on platform integrity, stability against overturning (via ties), and human-centric safety. The loads it is designed for are a fraction of shoring loads. For example, a heavy-duty shoring post may be rated to support 50,000 lbs (222 kN), whereas an entire 7-foot bay of heavy-duty scaffolding might be rated for a total of 75 lbs per square foot.

Duration, Material, and Safety Differences

The differences extend to every other aspect of the systems.

- Duration: Shoring’s duration is tied to the structural event it is preventing. For falsework, it remains until the concrete achieves a specified percentage of its 28-day design strength. For trench shoring, it is removed as the trench is backfilled. Scaffolding’s duration is tied to the task being performed: painting, cladding, or maintenance, which could be days, weeks, or months.

- Material: As shoring is designed for high compressive strength, it uses heavy-duty, thick-walled steel components, massive timbers, or structural steel beams. Scaffolding uses lighter-gauge steel or aluminum tubes and frames, designed to be strong enough for access loads but light enough for manual erection and transport.

- Safety: The primary safety risk in shoring is a sudden, catastrophic structural collapse due to load miscalculation, foundation settlement, or component failure. The primary safety risk in scaffolding is a fall from height due to platform failure, inadequate guardrails, or worker error.

Detailed Comparison Table – Shoring vs. Scaffolding

To clearly synthesize the scaffolding vs shoring distinctions, a direct comparison of their core attributes is invaluable. The following table breaks down the fundamental differences in purpose, engineering, and application, providing a quick-reference guide for technical professionals. This visual summary distills the critical difference between shoring and scaffolding into an easily digestible format.

| Feature | Shoring | Scaffolding |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Purpose | Structural Support: To prop up or brace an unstable structure. | Worker Access: To provide a safe, elevated working platform. |

| Load Type Handled | Vertical (Dead/Live Loads): e.g., weight of wet concrete, a building, or a floor.

Lateral Loads: e.g., pressure from earth, wind, or water. |

Vertical (Live Loads): e.g., weight of workers, tools, and light materials.

Lateral Loads: e.g., wind on the structure itself. |

| Load Transfer Path | From the unstable structure -> through the shoring system -> to a solid foundation (ground). | From the working platform -> through the scaffold frame -> to the ground. |

| Primary Materials | Heavy-duty steel (e.g., H-beams, post shores, modular shoring frames), heavy timber. | Steel or aluminum (for frame components), timber or steel (for platforms). |

| Common Examples | Falsework (slab support), trench shoring, raking shores (wall support), facade retention. | Frame scaffolds, modular systems (Ringlock, Cuplock), suspended scaffolds, stair towers. |

| Key Safety Risk | Structural Collapse: Sudden failure under load due to miscalculation, overloading, or foundation failure. | Falls from Height: Workers falling from platforms, or objects falling onto personnel below. |

| Engineering Focus | Compressive Strength: Ability to resist axial loads without buckling or failing. | Stability & Ergonomics: Platform integrity, guardrail compliance, and lateral stability (tying). |

| Keyword Analogy | “A Crutch” – Supports a weakened structure. | “A Ladder/Platform” – Provides access to a structure. |

This table explicitly demonstrates that while both can be constructed from shoring scaffolding systems components, their engineering functions are not interchangeable. A system designed for access (scaffolding) must never be used for primary structural support (shoring) unless it has been specifically engineered and rated for that purpose by a qualified professional. In such cases, the system is functionally being used as shoring, and its access properties are secondary.

Engineering Standards and Compliance

The design, erection, use, and dismantling of all temporary works are governed by stringent, legally binding standards to ensure site safety. These regulations are not optional guidelines; they are the minimum requirement for protecting workers and the public. In the United States, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) is the primary regulatory body, with its standards documented in the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR). These standards mandate that all temporary systems be designed by a qualified person and inspected by a competent person.

In Europe, standards from the European Committee for Standardization (CEN) are paramount, such as the EN 12811 series for scaffolding and EN 12812 for falsework (shoring). These standards provide highly detailed technical specifications for material properties, design calculations, testing procedures, and required safety factors. Both OSHA and EN standards place a heavy emphasis on documented design, formal training for erectors, and rigorous inspection protocols. Non-compliance can result in severe penalties, project shutdowns, and, in the event of an accident, criminal liability.

OSHA and EN Standards for Temporary Works

OSHA’s regulations for temporary works are specific and distinct. OSHA 29 CFR 1926 Subpart L is dedicated entirely to Scaffolding. It mandates that scaffolds must be designed by a qualified person and capable of supporting their own weight plus at least four times their maximum intended load (a 4:1 safety factor). It provides explicit rules for guardrail heights, platform construction, safe access, and tie-in spacing. This standard is focused on preventing falls and ensuring a stable access platform.

Conversely, shoring is covered under different standards based on its application. Subpart P (Excavations) details the requirements for trench shoring, mandating that protective systems be used in any trench 5 feet or deeper. It requires a registered professional engineer to design shoring for excavations deeper than 20 feet. Subpart Q (Concrete and Masonry) governs the use of shoring and reshoring (falsework) for concrete structures. It focuses on the system’s ability to support the total load of wet concrete and construction forces, and it dictates the process for safely stripping forms and transferring loads to the cured structure.

Inspection Protocols and Maintenance Guidelines

A temporary work system is only as safe as its installation and maintenance. Both OSHA and EN standards require that a “competent person” (one who can identify existing and predictable hazards and has the authority to take corrective measures) must oversee the erection, modification, and dismantling of all shoring and scaffolding systems. This competent person is also responsible for conducting regular inspections.

This inspection protocol is not arbitrary. It must occur before the first use, at the start of every shift, and after any event that could compromise the system’s integrity—such as a high-wind event, a vehicle collision, or any modifications. A “scaffold tag” system (Green for “Safe for Use,” Red for “Unsafe – Do Not Use”) is a common best practice for communicating the inspection status to all workers. Maintenance involves checking that all components are free from damage (bent tubes, cracked welds, split planks), all connections are secure, and the foundation (sole plates) remains level, firm, and stable.

Cost and Project Management Considerations

From a project management and procurement perspective, shoring and scaffolding represent two very different types of costs. The procurement process, rental models, and labor requirements are distinct and must be budgeted for accordingly. A project manager who budgets for “scaffolding” when what is required is “shoring” will find their budget and timeline completely unworkable.

The cost of scaffolding is typically calculated based on the area of access required (square meters or square feet) and the duration of the rental. The key variables are the height of the scaffold, the number of working platforms, and the duty rating required. The primary cost driver is often the skilled labor required for erection and dismantling. The cost of shoring, on the other hand, is calculated based on the load that must be supported (kilonewtons or kips). It is an engineered solution, and its cost includes the detailed structural design, the heavy-duty, high-capacity rental materials, and the precision installation by a specialized crew. The material cost per component is significantly higher than for scaffolding.

Material Costs, Labor, and Project Duration

Shoring materials are inherently more expensive. A heavy-duty steel shoring post designed to support 50 kN is a more specialized and costly item than a standard scaffolding tube. Because shoring is often tied to the critical path of a project (e.g., concrete cannot be poured until the falsework is in place), its duration on-site is precisely managed. Any delays in its installation or removal can halt the entire project. Labor for shoring is highly specialized, often requiring certified welders or riggers, in addition to competent erectors who can read and implement complex engineering drawings.

Scaffolding labor, while also requiring trained and certified crews, is more widely available. The materials are designed for manual handling and rapid assembly, optimizing labor costs. The duration of a scaffold rental is tied to the finishing trades (painting, cladding, EIFS) which, while important, may not be on the same critical-path level as concrete curing. Understanding this difference between shoring and scaffolding in procurement is key to accurate project bidding and management.

Optimization of Equipment and Reusability

Modern shoring scaffolding systems are designed for reusability. Modular systems, in particular, offer significant optimization. A system like Ringlock, for example, can be used to build a highly versatile access scaffold. Those same components (standards, ledgers, and especially heavy-duty base jacks and u-heads) can also be used, with proper engineering, to build a shoring tower for light-to-medium-duty applications. This is the “overlap” that often causes confusion.

However, optimization requires expertise. A contractor cannot simply decide to use their access scaffold as shoring. A qualified engineer must redesign the system, using the known component capacities, to act as shoring. This typically involves drastically reducing the spacing of vertical standards, adding significant plan bracing, and ensuring every component is used within its rated compressive load limit. True optimization comes from using the right equipment for the right job, and reusability is a factor in choosing a system supplier that offers a wide range of compatible components for both access and support.

Common Mistakes and Failure Cases

The most catastrophic failures in temporary works often stem from a fundamental misunderstanding of the difference between shoring and scaffolding . The single most common and deadly mistake is using access scaffolding components for a shoring application. A standard light-duty scaffold frame is designed to support a few workers and their tools. It is not, under any circumstances, designed to support the load of a 10-inch-thick wet concrete slab, which can exert a downward force of over 125 pounds per square foot, plus construction loads. When this is attempted, the slender scaffold legs, which are not designed for high axial compression, buckle, leading to a catastrophic and progressive collapse.

This confusion is also related to the difference between scaffolding and shuttering . Shuttering (or formwork) is the “mold” that holds the wet concrete in its desired shape. Shoring (or falsework) is the support structure that holds the shuttering and the concrete up. Scaffolding is a separate system that might be erected next to the formwork to allow workers to access it, but it should never be part of the support system unless explicitly designed as such.

Design Errors in Shoring Systems

Shoring failures, even when the correct equipment is used, are often traced back to critical design or installation errors.

- Foundation Failure: The most common error. The massive loads collected by the shoring posts must be transferred to a foundation. If this foundation is uncompacted soil, a lower-level uncured slab, or even asphalt, the concentrated load from the post can “punch” through, leading to settlement and failure. Proper sole plates and ground-bearing-pressure calculations are essential.

- Inadequate Bracing: A tall shoring post, like a scaffold, is strong in compression but weak against lateral movement. Without adequate horizontal and diagonal bracing, a shoring system can “rack” or “kick out,” leading to a collapse.

- Miscalculation of Loads: Underestimating the weight of wet concrete, failing to account for dynamic loads (like the “pumping” of concrete), or not factoring in the weight of all materials can lead to the system being overloaded from the start.

Improper Assembly of Scaffolding Structures

Scaffolding failures are more often linked to human factors—both in assembly and in use.

- Inadequate Tying: The most common cause of a scaffold collapse. Failure to install ties to the building, or installing them at incorrect intervals, allows the scaffold to pull away from the building or be blown over by wind.

- Lack of Guardrails/Planks: Failure to install guardrails, mid-rails, and toeboards, or leaving gaps in the platform planking, directly leads to the number one risk: falls from height.

- Overloading: Workers may not understand the “duty rating” of a scaffold and may overload a platform with an entire pallet of bricks or heavy materials, leading to a localized platform failure.

- Poor Foundation: Just like shoring, a scaffold built on soft, uneven ground without proper base plates and sole plates is unstable from the first level.

Decision-Making Guide – When to Use Shoring vs. Scaffolding

The decision-making process is, in fact, very simple. It is not a choice between the two, but an identification of the need. The project manager or engineer must ask one simple question: “What is the primary task this temporary structure must perform?”

- If the answer is: “It must support the weight of a slab/wall/roof,” “It must hold back the earth in a trench,” or “It must prevent a structure from falling over,” the required solution is SHORING.

- If the answer is: “I need to get workers to that facade to paint it,” “We need a platform to install windows,” or “My crew needs to stand at that height to weld a pipe,” the required solution is SCAFFOLDING.

There should never be an “either/or” debate. They are two different tools for two different jobs. If a project requires both—for example, supporting a new concrete slab (shoring) and providing access for workers to finish the slab edge (scaffolding)—then two separate, or one properly engineered integrated, system(s) must be planned and budgeted for.

Safety Guidelines and Best Practices

Whether using shoring or scaffolding, safety is paramount and begins with a non-negotiable set of best practices.

- Use the Right System: Never use access scaffolding for shoring.

- Qualified Design: Ensure any shoring system, and any scaffold over a certain height (e.g., 125 ft in the US, or of a complex design), is designed by a qualified, registered professional engineer. 3* Competent Erection: Erection, modification, and dismantling must only be performed by trained, certified, and competent personnel under the supervision of a competent person.

- Rigorous Inspection: The “competent person” must inspect the system before every shift and after any adverse event. Trust the tag—if it’s red, do not use it.

- Stable Foundation: Never erect any temporary structure on unstable, uncompacted, or uneven ground without proper sole plates, mudsills, and shims to create a level, stable foundation.

- Full Compliance: Ensure the system fully complies with all local and national standards (e.g., OSHA, EN). Do not cut corners on components, bracing, or safety features like guardrails.

Real-World Applications and Case Studies

Case Study 1: Shoring (Falsework) in High-Rise Construction

- Project: A 40-story commercial office tower.

- Application: To construct the floor slabs, a “flying form” system is used. For the first few levels and the large-span podium, a massive system of heavy-duty steel shoring frames and post shores is erected.

- Engineering: Engineers calculated the dead load of the 12-inch-thick post-tensioned concrete slab, plus live loads. The shoring system was designed to transfer these loads (thousands of kips) through the columns of the levels below. The shoring remained in place until the concrete achieved 75% of its 28-day strength, confirmed by cylinder break tests.

- Contrast: Separate scaffolding stair towers were erected to provide workers access to the shoring and formwork levels.

Case Study 2: Scaffolding in Facade Restoration

- Project: A 100-year-old historic stone-facade university building.

- Application: The entire facade required masonry inspection, repointing, and cleaning.

- Engineering: A modular (Ringlock) scaffolding system was erected from the ground up, enveloping the building. It was tied into the structure’s mortar joints at every 4-meter vertical and 6-meter horizontal interval. The system provided multiple, fully-planked working levels, complete with guardrails, toeboards, and debris netting.

- Contrast: The scaffold supported only the workers, their hand tools, and small buckets of mortar. It supported zero load from the building itself. At one point, a small, damaged archway required support during repair. This required a separate, small-scale shoring system (dead shores and needles) to be installed, independent of the access scaffold.

Conclusion – Choosing the Right System with BFS Industries Expertise

In conclusion, the difference between shoring and scaffolding is absolute and fundamental. Shoring is a temporary structural support system engineered to bear massive loads and prevent collapse. Scaffolding is a temporary worker access system engineered to provide a safe, ergonomic platform to prevent falls. One supports the structure, the other supports the personnel. Confusing the two, or misusing the equipment, is one of the most significant and preventable risks on a construction site.

Understanding this core distinction is the first step toward a safer, more efficient, and more professional project execution. Choosing the correct, compliant, and most cost-effective shoring scaffolding systems requires expertise. For any project, from complex industrial maintenance to new high-rise construction, consulting with an industry leader is essential. BFS Industries provides world-class expertise in both engineered access scaffolding and heavy-duty shoring systems. We ensure your project is supported by the correct temporary works solution, engineered for safety and performance from the ground up.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What is the main difference between shoring and scaffolding?

The main difference is their purpose. Shoring is a temporary structural support system designed to bear the weight of a structure (like a wall or concrete slab) to prevent it from collapsing. Scaffolding is a temporary access platform designed to provide workers with a safe, elevated place to stand, along with their tools and materials. In short: shoring supports the building; scaffolding supports the workers.

Can scaffolding be used for shoring purposes?

Generally, no. Standard access scaffolding is not engineered to handle the massive, concentrated loads that shoring is required to support. Attempting to use regular scaffolding as shoring is extremely dangerous. However, some heavy-duty modular system components (like those used in Ringlock or Cuplock) can be specifically engineered by a qualified professional for use in both heavy-duty access and light-to-medium-duty shoring applications. This must be a formal, calculated design.

What materials are used in shoring systems?

Shoring systems are built to handle immense compressive forces. Therefore, they are typically constructed from heavy-duty materials like high-strength steel (e.g., I-beams, H-beams, thick-walled steel posts, modular shoring frames) or large-dimension, structural-grade timber.

When should shoring be used instead of scaffolding?

Shoring must be used any time you need to support a structural element that cannot support itself. This includes: supporting wet concrete formwork (falsework), bracing the sides of an excavation (trench shoring), supporting a wall or roof during demolition or renovation, or temporarily bracing a structure damaged by fire or impact. You would use scaffolding when you simply need to get workers and their tools to an elevated area to perform tasks like painting, welding, or bricklaying.

What safety standards apply to shoring and scaffolding systems?

Both are heavily regulated. In the U.S., OSHA (Occupational Safety and Health Administration) provides specific standards: 29 CFR 1926 Subpart L for Scaffolding and Subpart P (Excavations) and Subpart Q (Concrete) for shoring. In Europe, key standards include EN 12811 (Scaffolding) and EN 12812 (Falsework/Shoring). These standards dictate design, load capacity, inspection, and safe use.