- Published:

- Written by: B.F.S Industries

Types of Reinforcement in Construction – A Comprehensive Guide

FREE DOWNLOAD – B.F.S. HOLDING

Explore the full spectrum of services and industries covered by B.F.S. Holding.

The structural integrity and longevity of modern civil engineering projects hinge critically on the effective implementation of reinforcement systems. Understanding the various types of reinforcement in construction is essential for engineers, architects, and site managers to correctly specify materials that can meet the complex performance demands of contemporary infrastructure, ranging from high-rise buildings to critical marine environments. Reinforcement, fundamentally, is the material embedded within concrete or masonry to counteract the weak tensile strength inherent to these brittle materials, ensuring structures can safely handle bending, shear, and torsional forces. This article, presented by the experts at BFS Industries in advanced structural solutions, provides a detailed analysis of the different reinforcement materials available, their mechanical properties, specific applications, and the rigorous standards governing their use in structural systems globally.

What Is Reinforcement in Construction?

Reinforcement refers to the strategic placement of secondary materials within a primary structural matrix, most commonly concrete, to enhance its tensile resistance. Concrete possesses extremely high compressive strength, meaning it resists being crushed, but fails rapidly when subjected to pulling or stretching forces (tension). By embedding high-tensile materials, the composite structure—known as Reinforced Concrete (RC)—effectively transfers tensile stress to the reinforcement. This engineered synergy ensures the structural element, whether a beam, slab, or column, remains monolithic and serviceable under load, preventing catastrophic failure due to cracking and deformation.

The mechanical coupling between the concrete and the reinforcement material is critical for load transfer; the reinforcement must be bonded securely to the surrounding matrix. In the case of steel rebar, this bonding is achieved through the chemical adhesion of the concrete paste and the physical interlocking provided by surface deformations (ribs or indentations) on the bar. The selection of reinforcement type directly dictates the structural element’s ultimate capacity and determines its durability profile, particularly its resistance to environmental factors like moisture and chloride ingress, which are primary drivers of corrosion in traditional steel.

Importance of Reinforcement in Modern Construction

Reinforcement is indispensable for constructing durable, economical, and high-performance structures that are capable of resisting both static and dynamic loads. It allows engineers to design slender, efficient members rather than relying on massive, purely compressive concrete sections, thereby conserving materials and optimizing usable space. Beyond simply bearing static weights, reinforcement provides essential ductility, enabling the structure to absorb and dissipate energy during extreme events such as earthquakes or high winds, offering visible warning signs (cracks) before total collapse, a fundamental requirement in modern seismic design codes.

Furthermore, reinforcement controls crack width due to temperature changes and shrinkage, ensuring the long-term impermeability of the concrete cover and protecting the internal structure. The global imperative for infrastructure development, coupled with increasingly aggressive environmental conditions (e.g., coastal exposure, de-icing salts), demands advanced and specialized reinforcement materials. This has driven the industry toward exploring alternatives to conventional steel, necessitating a thorough understanding of all available types of reinforcement materials to ensure optimal performance over a structure’s intended service life.

Main Types of Reinforcement Materials

The landscape of structural reinforcement extends far beyond traditional steel rebar, encompassing a variety of metallic and composite materials, each with unique mechanical, electrochemical, and cost characteristics. The choice between these materials is a complex engineering decision, balancing initial construction costs against lifecycle durability and required performance in specific environments. Understanding the core attributes of each material is the first step in successful structural specification.

1. Steel Reinforcement Bars (Rebars)

Steel reinforcement bars, or rebars, represent the most common and standardized form of reinforcement globally, primarily due to their high tensile strength, excellent ductility, and mechanical compatibility with concrete. Steel rebar is primarily composed of carbon steel alloys, which offer a high yield strength to effectively transfer and absorb tensile loads. They are universally specified for use in foundational elements, columns, beams, and slabs in virtually all conventional Reinforced Concrete construction.

2. Mild Steel and Deformed Bars

Mild steel bars possess a smooth surface and lower yield strength, making them historically significant but less common in new construction due to poor bond strength. Deformed bars, conversely, feature ribs or patterns rolled onto their surface, dramatically increasing the mechanical bond and the efficiency of stress transfer between the concrete and the steel. This superior bonding capacity and higher tensile strength make deformed bars the standard for high-strength reinforcement work in building construction today.

3. Galvanized and Epoxy-Coated Rebars

In environments with moderate to high corrosion risk, carbon steel’s susceptibility to rust is a major concern. Galvanized rebars are coated in a layer of zinc, providing cathodic protection that sacrifices the zinc layer to protect the steel. Epoxy-coated rebars (ECR) feature a thin layer of fusion-bonded epoxy powder, acting as a physical barrier against moisture and chlorides. ECR is widely used in bridge decks and parking garages but requires extremely careful handling to prevent damage to the coating, which could compromise its protective capabilities.

4. Stainless Steel and Carbon Steel Reinforcement

Stainless steel rebars are the highest-performing metallic reinforcement solution for corrosion resistance, utilizing chromium content to form a passive, protective oxide layer. Although they carry a high initial material cost, their virtually maintenance-free durability makes them cost-effective over a long lifecycle in highly aggressive environments, such as marine structures or chemical plants. Standard carbon steel reinforcement remains the economical default for non-aggressive, interior applications where concrete cover provides sufficient initial protection.

5. Prestressing Steel and Tendons

Prestressing steel, utilized in pre-tensioned and post-tensioned concrete, involves high-strength steel strands or bars that are tensioned before or after concrete curing. This introduces a pre-compression force into the concrete element, counteracting the expected tensile stresses from applied loads. This technique significantly enhances load-bearing capacity, controls cracking, and allows for much longer spans in structures like long-span bridges and large roof slabs compared to passively reinforced concrete.

6. FRP (Fiber-Reinforced Polymer) Bars

Fiber Reinforced Polymer (FRP) rebars, including GFRP (Glass), CFRP (Carbon), and AFRP (Aramid), are advanced composite materials designed to address the corrosion limitations of steel. FRP bars are non-metallic, non-magnetic, and chemically inert, offering exceptional corrosion resistance and a high strength-to-weight ratio. These characteristics make fiber reinforced polymer (FRP) rebars the preferred choice for marine infrastructure, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) suites, and environments exposed to harsh chemicals.

7. Welded Wire Mesh and Fabric Reinforcement

Welded wire reinforcement (WWR), also known as welded wire fabric, consists of orthogonal arrays of steel wires welded together at their intersections. This material is primarily used for slab-on-grade applications, pavements, and precast elements to control shrinkage cracking and provide minimum temperature reinforcement. WWR is highly efficient for large, flat areas, speeding up installation and ensuring consistent spacing compared to individually placed rebars.

8. Fiber and Composite Reinforcement Materials

This category includes micro-scale fiber reinforcement, where discrete fibers are dispersed throughout the concrete mix itself, creating “Fiber Reinforced Concrete” (FRC). Materials such as steel fibers, synthetic fibers (polypropylene, nylon), and natural fibers (cellulose) enhance the concrete’s post-crack residual strength, impact resistance, and abrasion resistance. They often complement, rather than replace, bar or mesh reinforcement, particularly in industrial floors and shotcrete applications.

Applications of Reinforcement in Construction

The strategic deployment of reinforcement is tailored to the specific functional and load-bearing requirements of the structure, encompassing virtually every element in civil and building construction. Proper design accounts not only for the magnitude of forces but also the environmental conditions to which the element will be exposed, guiding the choice between conventional and specialized materials.

The layout and secure placement of rebar are as critical as the bar selection itself. During the concrete casting process, maintaining precise cover and minimizing rebar movement is crucial for the final performance of the composite structure. This involves rigorous adherence to specifications, especially concerning spacing and tying. Furthermore, the selection of appropriate Concrete pouring methods is essential to ensure proper concrete flow around densely packed reinforcement cages, preventing honeycombing or voids which compromise the integrity of the element.

Reinforcement in Concrete Structures

In primary concrete structures like beams, the reinforcement cage provides resistance against bending moments, with longitudinal bars resisting flexural tension and stirrups resisting shear forces. In slabs, two-way reinforcement is typically used to handle distributed loads and punching shear stresses. Effective continuity in reinforcement is vital, particularly at joints and intersections; poor lapping practices or inadequate vibration can lead to significant structural flaws, potentially resulting in premature concrete failure or the formation of cold joints in concrete columns.

Wall and Foundation Reinforcement

Foundations, including strip, raft, and pile caps, require robust reinforcement to manage the varying stresses imposed by the superstructure and differential soil movements. Walls, especially shear walls in high-rise construction and retaining walls, rely on vertical and horizontal reinforcement grids to resist lateral forces (wind, seismic) and overturning moments. Precise placement of the reinforcement cage within the formwork is non-negotiable, and formwork solutions like those offered for Concrete Column Formwork must accommodate the often-dense rebar arrangements without impeding concrete placement.

Bridge, Tunnel, and High-Rise Reinforcement

These complex structures often represent the pinnacle of reinforcement engineering, requiring specialized materials for extreme durability. Bridges and tunnels, frequently exposed to water, de-icing salts, or corrosive soil, are increasingly specified with corrosion-resistant options like FRP or stainless steel to achieve service lives exceeding 100 years. High-rise buildings demand high-yield strength steel (up to 600 MPa) to resist massive axial compression and wind-induced bending moments, often requiring complex, pre-fabricated reinforcement modules to maintain construction speed and quality control.

Standards and Material Specifications

The performance and safety of reinforced concrete structures are governed by stringent national and international specifications. These standards ensure material quality, define acceptable dimensions and tolerances, and provide guidelines for testing and compliance, creating a universal language for structural engineers and material suppliers. Adherence to these specifications is mandatory for structural acceptance and long-term performance.

The specification of reinforcement goes beyond chemical composition and mechanical strength; it also defines surface geometry (rib pattern), allowable bend radii, and testing protocols. For instance, the specified tensile strength must not only meet the required yield point but also exhibit sufficient ductility to ensure the steel can deform significantly before fracture, preventing sudden, brittle failures. Project managers must implement strict quality control procedures on site, comparing mill certificates against site testing data and visually inspecting bars for surface defects, rust, or improper handling before placement.

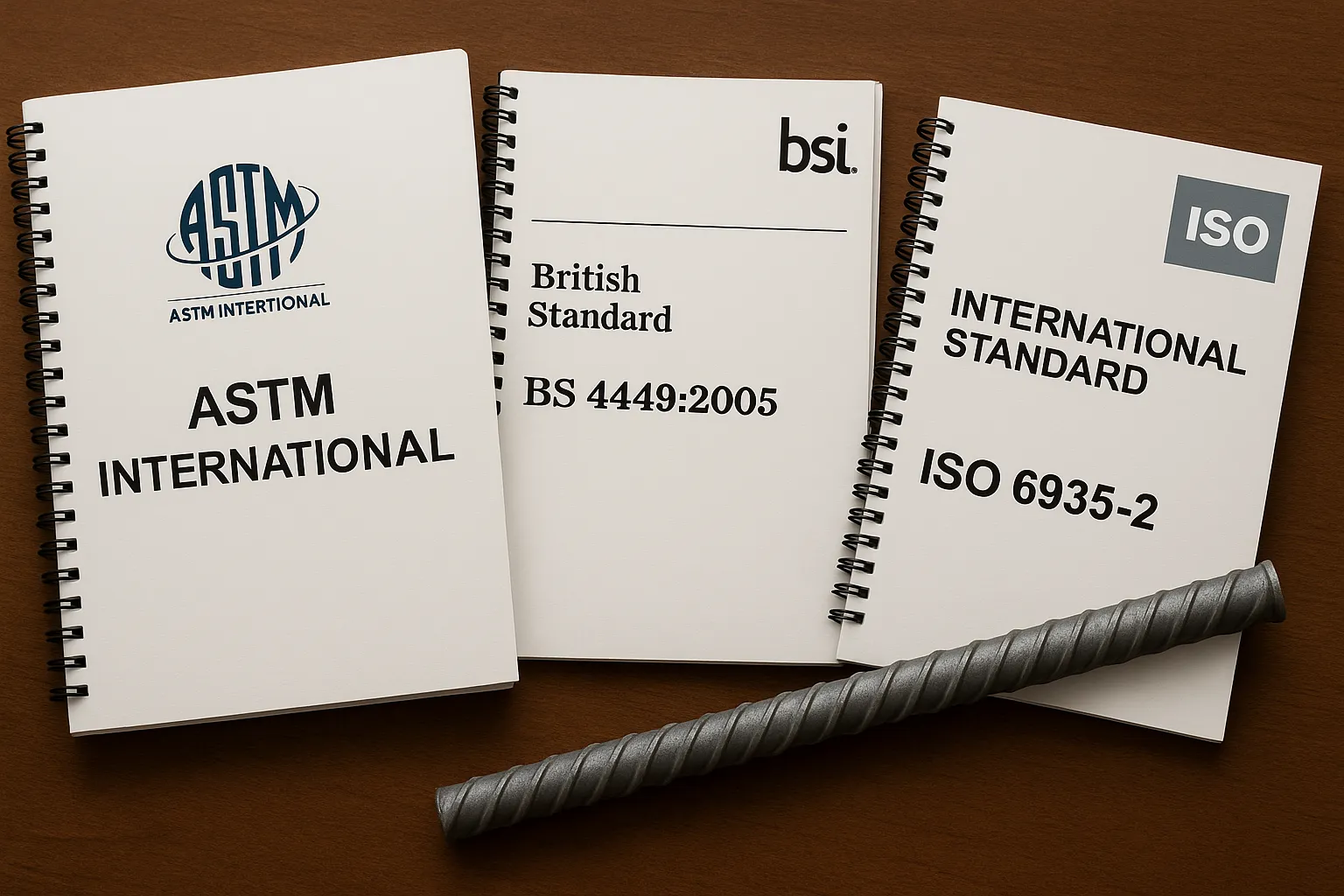

ASTM, BS, and ISO Standards for Reinforcement Steel

The most prominent global standards organizations dictate the specifications for reinforcement steel. ASTM International (e.g., ASTM A615, A706 for welding) is widely used in the Americas, defining grades based on minimum yield strength (e.g., Grade 60, 420 MPa). British Standards (BS 4449) are often referenced in European and Commonwealth nations. Meanwhile, ISO standards provide globally harmonized specifications, promoting uniformity in material testing and certification. These documents are the authoritative source for steel properties, including chemical composition, dimensions, and testing frequency.

Testing, Inspection, and Quality Assurance

Quality assurance involves both laboratory testing and site inspection. Testing includes tensile tests to confirm yield and ultimate strength, bend/re-bend tests to confirm ductility, and chemical analysis to verify alloy composition. On-site inspection focuses on cover depth verification (using covermeters), lap length compliance, bar spacing, and the cleanliness of the reinforcement before the pour. Proper quality assurance documentation ensures traceability of materials from the supplier to the final structure, mitigating the risk of structural failure due to substandard materials.

Advantages and Limitations of Each Reinforcement Type

The decision to select a particular type of reinforcement material is a trade-off that balances mechanical performance, cost, and durability, often determined by the environment and the specific structural function. No single material is universally optimal; instead, the selection must be an informed engineering judgment.

Standard carbon steel offers high strength and excellent bond characteristics but its primary limitation is its susceptibility to corrosion, which leads to rust expansion and concrete spalling. Galvanized and epoxy-coated bars mitigate this issue but introduce complexity in installation and maintenance. Modern composites, such as FRP, eliminate corrosion risk and offer superior strength-to-weight ratios, but they exhibit linear elastic behavior (low ductility) and higher initial material costs, requiring specialized design considerations compared to steel’s highly ductile properties.

Corrosion Resistance and Strength Characteristics

The critical advantage of stainless steel and FRP over standard carbon steel is corrosion resistance, making them invaluable in high-chloride environments. Standard carbon steel relies entirely on the alkaline concrete environment for passivation, a protection that breaks down when chlorides penetrate the concrete cover. In terms of strength, high-yield deformed steel and prestressing strands offer the highest tensile capacities, while FRP bars often provide superior ultimate strength at a much lower modulus of elasticity, meaning they stretch more than steel under the same load.

Cost, Sustainability, and Durability

Cost remains the most significant barrier to the widespread adoption of advanced materials, with FRP and stainless steel having substantially higher initial costs than carbon steel. However, durability is a lifecycle calculation: while carbon steel is cheaper upfront, its maintenance and replacement costs in aggressive environments can far exceed the initial saving. Sustainability is another emerging factor; steel is highly recyclable, whereas the environmental impact of composite FRP production is a growing area of industry research and improvement.

Emerging Trends and Innovations in Reinforcement

The construction industry continues to seek materials that offer the strength of steel with superior durability and installation efficiency. Emerging trends focus on nanotechnologies, self-healing concepts, and advanced hybrid systems that combine the best attributes of multiple materials to achieve optimized performance envelopes.

These innovations are driven by the need to extend the service life of critical infrastructure while minimizing disruption and repair costs. For instance, the combination of traditional rebar with micro-fibers, or the use of hybrid GFRP-steel cages in specific corrosive zones, provides targeted protection where it is most needed without prohibitive cost increases across the entire structure. The goal is to move towards performance-based specification, where the required service life dictates the necessary material blend.

Fiber-Reinforced Concrete and Hybrid Reinforcement Systems

Fiber-Reinforced Concrete (FRC) has evolved from simple crack control to engineered high-performance material, utilizing high-volume synthetic or steel fibers to significantly enhance concrete’s fracture toughness and ductility. Hybrid reinforcement systems combine rebar cages with FRC, using the fibers to control micro-cracking and the bars to carry bulk tensile loads. This synergetic approach leads to structures with exceptional resistance to fatigue, impact, and thermal stresses, often exceeding the performance of traditional RC.

Smart and Nano-Reinforcement Technologies

Smart reinforcement includes bars and composites embedded with fiber optic sensors or micro-electromechanical systems (MEMS) capable of monitoring strain, temperature, and corrosion levels in real-time. This allows for continuous structural health monitoring (SHM), enabling preemptive maintenance. Nano-reinforcement, such as the use of carbon nanotubes or nanoclay, aims to enhance the concrete matrix itself, improving density, strength, and durability at the microscopic level, thereby providing an intrinsic defense against deterioration.

Comparison Table – Traditional vs. Modern Reinforcement Materials

| Feature | Carbon Steel (Deformed) | Epoxy-Coated Steel (ECR) | Stainless Steel | FRP (GFRP/CFRP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tensile Strength | High | High | High | Very High (especially CFRP) |

| Corrosion Resistance | Low (relies on concrete) | Medium (if coating intact) | Excellent | Inert (Excellent) |

| Ductility | High (Ductile failure) | High (Ductile failure) | High | Low (Linear elastic/Brittle) |

| Modulus of Elasticity | High (200 GPa) | High (200 GPa) | High | Low (35-150 GPa) |

| Magnetism | Magnetic | Magnetic | Non-Magnetic grades available | Non-Magnetic |

| Relative Cost | Low (Baseline) | Medium | High | High |

| Primary Application | General Construction | Bridge Decks, Parking Garages | Marine, Chemical Plants | MRI, Tunnels, Coastal |

Best Practices for Selecting Reinforcement Type

The process of selecting the appropriate reinforcement type must be guided by a systematic engineering evaluation that moves beyond simple material cost to consider the entire service life of the structure. Engineers must first define the required service life and the aggressiveness of the environment (e.g., chloride concentration, freeze-thaw cycles, seismic zone). This defines the necessary durability class.

Once the durability requirements are established, the mechanical performance criteria—including strength, stiffness (Modulus of Elasticity), and ductility—must be evaluated against the proposed material’s properties. For instance, while FRP offers excellent durability, its low stiffness requires a design that controls deflection and cracking more stringently than steel. The specification must also account for constructability, ensuring that the selected material can be handled, tied, and placed efficiently according to the project’s quality and schedule requirements.

Conclusion – Reinforcement Innovation with BFS Industries Expertise

The evolution of reinforcement materials reflects the industry’s increasing demand for resilient, long-lasting, and structurally efficient infrastructure. The selection of the correct types of reinforcement in construction—from high-strength carbon steel to advanced FRP composites—is a decision that fundamentally shapes a structure’s ability to withstand the test of time and environment. Ensuring the proper placement, continuity, and concrete cover for any chosen material is just as vital as the material selection itself. As a leading concrete wall formwork supplier and innovator in construction technologies, BFS Industries provides not only advanced formwork systems but also the comprehensive knowledge base necessary for seamless integration with all modern reinforcement systems. Partnering with BFS Industries ensures that your project benefits from industry-leading expertise in both reinforcement engineering and the formwork precision essential to realize its full structural potential.

FAQ (Frequently Asked Questions)

What are the main types of reinforcement used in construction?

The main types of reinforcement used in construction include: Carbon Steel Reinforcement Bars (Rebars), which are the most common; Coated Steels (Galvanized and Epoxy-Coated) for corrosion protection; Stainless Steel Rebars for extreme corrosive environments; and Fiber-Reinforced Polymer (FRP) Bars (GFRP, CFRP), which are non-metallic and highly corrosion-resistant composites.

What is the difference between steel and FRP reinforcement?

The primary difference is material composition and properties. Steel (carbon) is metallic, ductile, magnetic, and susceptible to corrosion, but has a high modulus of elasticity (stiffness). FRP (Fiber-Reinforced Polymer) is a composite material (fibers in a resin matrix), non-metallic, inert to corrosion, non-magnetic, and has a lower modulus of elasticity (less stiff), exhibiting linear elastic (brittle) failure.

Which type of reinforcement is most corrosion-resistant?

FRP (Fiber-Reinforced Polymer) rebars and stainless steel rebars are the most corrosion-resistant types of reinforcement. FRP is chemically inert and cannot rust, making it superior in salt-water and chemical exposure. Stainless steel forms a passive chromium oxide layer that provides exceptional resistance, though it is more costly than standard carbon steel.

What standards govern reinforcement materials in construction?

Reinforcement materials are governed by international and national standards such as ASTM (American Society for Testing and Materials), BS (British Standards), and ISO (International Organization for Standardization). These standards define the chemical composition, mechanical properties (yield strength, ductility), dimensions, and testing requirements for different grades and types of reinforcement steel and composite bars.

How does BFS Industries support advanced reinforcement systems?

BFS Industries supports advanced reinforcement systems by providing precision formwork solutions, such as high-quality concrete wall formwork supplier and Concrete Column Formwork systems, that accommodate complex reinforcement cages. Their expertise ensures that regardless of the specialized reinforcement material chosen (e.g., steel or FRP), the formwork allows for correct placement, concrete cover, and precise alignment critical for the structure’s designed performance.